Introduction

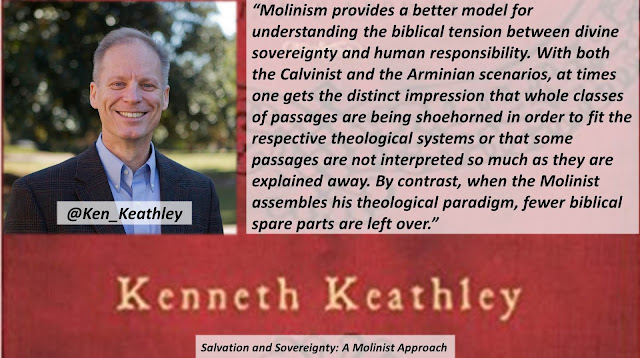

Among the many theological details that Christians discuss, the interaction between God's sovereignty and man's free will has to be one of the most heated. A lot of this heat comes from the thought that the other side is compromising some important doctrines of the Christian faith, including evangelism, God's moral perfection, man's moral responsibility, the justice behind eternal punishment, and several others. Along with defending the truth of mere Christianity, Christian case-makers encounter challenges regarding these doctrines all the time. It is important that the Christian hold a view that remains faithful to the whole of the text of the Bible while maintaining logical consistency, for if either of those is sacrificed in our defense of the Christian worldview, the skeptic has a "logical" reason to doubt the truth of Christianity, and a stumbling block has been put between them and Jesus Christ.Traditionally this debate has been between Calvinism and Arminianism, and both have their problems that the skeptic can appeal to to justify their doubt; however, another historical view has been regaining favor as it has been further investigated and formulated by theologians and philosophers. That view is Molinism. This view combines the biblical and philosophical strengths of both Calvinism and Arminianism, removes their respective scriptural and logical liabilities all while remaining faithful to the doctrine of Biblical Inerrancy and logical consistency. Unfortunately, numerous caricatures have been presented by those who hold opposing views. Dr. Kenneth Keathley has written Salvation and Sovereignty: A Molinist Approach to clarify the misunderstandings and misrepresentations by explaining the details of Molinism and biblically and philosophically defending the view. This review will consist of my usual chapter-by-chapter summary and conclude with my thoughts and recommendations on the book.

Book Introduction

Keathley begins with his reasons for writing on the relationship between God's sovereignty and man's free will. Each side in the general debate passionately defends their position, and accusations often are leveled against the other side of denying some critical biblical teaching in how they attempt to model the relationship. Because of the heat that is usually associated with this debate, Keathley explains that his goal in this book is to approach the topic humbly, recognize agreement where it exists, and offer more biblically acceptable alternatives where necessary. His desire is that we do not debate to win, but rather discuss to discover what is true- to bring us all closer to the correct knowledge of our Creator and Savior.This debate is usually between Calvinists and Arminians. He explains that the traditional Calvinistic acrostic TULIP (Total depravity, unconditional election, limited atonement, irresistible grace, perseverance of the saints) grossly misrepresents the concepts articulated in the Canons of Dort, which the TULIP has been used to quickly summarize. Many modern Calvinists end up only holding to a couple of the doctrines of the TULIP and/or must redefine the doctrines before they are willing to identify as Calvinists. Because of those reasons, Keathley believes that the TULIP needs to be replaced with a series of doctrines that more accurately describe the concepts in the Canons of Dort and are more faithful to all the teachings of Scripture regarding God's sovereignty and man's free will. He believes that the new series can be found in the Molinist position.

Molinism holds that God is meticulously sovereign over His creation and that man has genuine free will. God uses His omniscience to accomplish this coexistent relationship. Keathley proposes that the TULIP acrostic should be replaced with ROSES (Radical depravity, Overcoming grace, Sovereign election, Eternal life, Singular redemption). He will go into the details of each of these in the up-coming chapters. However, before digging deeper into the items in the replacement acrostic, a biblical case must be made for its sourced doctrine- Molinism.

Chapter 1: The Biblical Case for Molinism

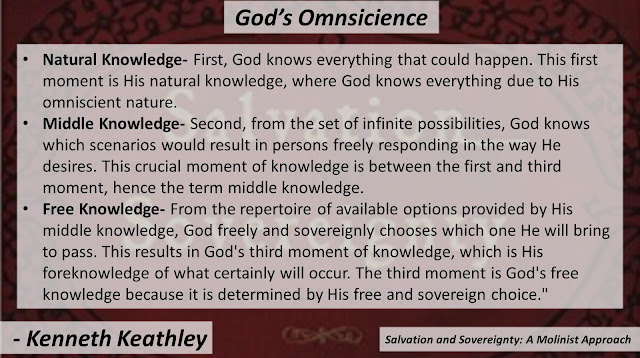

Keathley shows where the Bible affirms both God's meticulous sovereignty over His creation and the reality of man's libertarian free will (that man genuinely has the option to choose other than what he actually does choose). He explains that the doctrine of biblical inerrancy requires that any model must be able to accommodate both of those affirmations without compromising either. Keathley begins proposing the Molinist's model by explaining that Molinism recognizes three logical (not chronological) "moments" in God's knowledge: His natural knowledge, His free knowledge, and His middle knowledge. God's natural knowledge is His knowledge of all possibilities which is grounded necessarily in His omniscient nature. God's free knowledge is His knowledge of the world He freely chose to actualize (this world). His middle knowledge is a subset of His natural knowledge that specifically includes what free agents would do given any circumstance.Keathley provides several biblical passages that affirm each of these logical "moments" of God's knowledge. In his explanation of God's foreknowledge (knowledge of the future), he demonstrates where the Bible affirms that God's foreknowledge does not necessarily entail the absence of a genuine human choice, and he shows how this is also reflected in the everyday use of language. With the biblical foundation for God's meticulous sovereignty, man's libertarian free will, God's knowledge of all possibilities, God's knowledge of what people would choose in any circumstance, and God's knowledge of what is, all biblically grounded, the model can now be logically expounded. But before that exposition, one more issue must be addressed biblically.

Chapter 2: Does God Desire the Salvation of All?

Along with the debate about God's sovereignty and man's free will comes the question of whether God's desire for and offer of salvation to all is genuine or not. Keathley describes several options that have been put forth to answer this question within the different views of God's sovereignty and man's free will. The first option is that God has a single will. Those who hold this view, though, are divided as to what that single will is. Some believe that the will is love for all, which results in all eventually being saved (a form of universalism or inclusivism); while others hold that God's one will is to save the elect only, which results in a form of double-predestination of the unsaved (they are created for hell). Keathley explains that neither of these options is possible given the biblical data on the reality of eternal, conscious judgment (this removes the first singular will option) and that God desires that none should suffer eternal damnation (this removes second singular will option).The alternative to God possessing a singular will is that He possesses two wills. Again, those who take this view are also divided. One group holds that God's two wills are His revealed will and His hidden will, and the other group posit that God's two wills are His antecedent will and His consequent will. Using biblical inerrancy and logical consistency, Keathley demonstrates both the biblical and philosophical problems with the first option. He then puts forth the biblical data to demonstrate that both God's desire for and His offer of salvation to all are genuine. He presents the second of the two-wills option as biblically justified and logically consistent. With the genuineness of God's desire for and offer of salvation to all now also in place, Keathley begins his exposition of the replacement of TULIP.

Chapter 3: R Is for Radical Depravity

In the debate over God's sovereignty and man's free will, a few different general positions have taken shape. The most common are the two extremes of hard determinism and hard libertarianism. Hard determinism holds that man has no control over anything he does; this sacrifices moral responsibility for actions (though many hard determinists understand this and do attempt to prevent it). Hard libertarianism posits that man is so free in his decisions that God cannot know the decisions ahead of time, thus He is not truly omniscient. Historically determinists have moved more towards a "soft" determinism (or "compatiblism") that holds that man is free to do what he desires. Man's desires allow for only one option at any given point in time, so a desire is what determines the choice. Keathley grants that while the intention of the soft determinist is on the right track in positing that desires limit options, he shows that the view ultimately collapses back to hard determinism because God still determines the person's desires. Keathley interacts biblically and philosophically with different versions of these options to demonstrate that they are either not acceptable or are incomplete and that an alternative is necessary.He proposes that a soft libertarianism makes better sense of the biblical data and everyday experience while maintaining logical consistency. Soft libertarianism holds that desires do place a limit on decisions, but rather than only a single option, a range of options is available. It also proposes that ranges of options are made available at significant, character-building moments throughout the person's life. So, soft libertarianism does not posit absolute freedom (like hard libertarianism does) with all options available at all times, rather limited options are available at limited times. The person is truly free to choose among those options at those times, and as the choices are made, they affect the person's character which guides the desires (available options) in future decisions.

This is significant for making sense of the Fall of Adam. Keathley distinguishes between the freedom of responsibility and freedom of inclination. The freedom of responsibility affirms that man is fully, morally accountable for those things which he has the ability to do, while the freedom of inclination addresses the freedom to follow what one knows to be morally right. At the Fall of Adam, the freedom of responsibility did not take a hit (so man's choices are still his own, and he is morally responsible for them), rather it was the freedom of inclination that was marred. While man retains moral responsibility for his choices, because of the Fall of Adam, he is depraved to the point of not being able to choose what is right at all times (or even most times). Sanctification through Jesus Christ is the gradual restoration of the freedom of inclination. Radical Depravity posits that while man is fully, morally responsible for his chosen actions, he is not able not to sin. Man is radically depraved and sinful, and that depraved nature can only be overcome by God's grace.

Chapter 4: O Is for Overcoming Grace

Keathley offers that Irresistible grace (the "I" in TULIP) should be replaced with Overcoming Grace. He believes that the necessity of this is found in the fact that if God's call is, in fact, irresistible, then it logically follows that God's call to salvation to the non-elect is not genuine- why "call" someone to do something if you know that their acceptance of is impossible? The call to the non-elect becomes rhetorical lip service on God's part and not of a genuine nature. Keathley explains different ways in which this has been attempted to be addressed by various Calvinists. However, he shows that none of the views remain logically consistent or that they necessitate logical implications that violate Scripture elsewhere. To maintain logical consistency irresistible grace must violate Scripture, and to maintain biblical inerrancy it must violate logical consistency. Neither option is acceptable, thus an alternative must be posited.It is often argued that a resistible grace equates to man playing some kind of role with God in his salvation (synergism), thus being worthy of praise. Scripture explicitly denies that man's salvation is of his own doing in any part, so the question is, "how can a view be formulated that gives God all the glory for salvation and the sinner all the responsibility for rejection?" Keathley offers a model that takes what the Calvinist has properly identified and defends in Scripture and what the Arminian has properly identified and defends in Scripture yet Keathley leaves their respective violations aside. That model is found in the combination of (respectively) monergistic salvation (God alone, not man, is responsible for this objective good) and the resistibility of God's call (man alone, not God, is responsible for this objective evil).

Keathley presents the biblical necessity for this combination. The proof texts of both, respective positions are fully granted in this model, He explains that if one or the other is denied, then a large portion of Scripture must be rejected (the same claim both Calvinists and Arminians make against those who reject their respective proof texts). However, both opposing sides often claim that this combination is logically inconsistent by raising several objections. Keathley addresses the objections to demonstrate logical consistency (and more areas of agreement between Molinists and Calvinists and between Molinists and Arminians). The Overcoming Grace model posits that God's grace overcomes the radical depravity of a person if the person chooses to not resist it. Keathley concludes the chapter with twelve more clear advantages that the Overcoming Grace model possesses over the Irresistible Grace model.

Chapter 5: S Is for Sovereign Election

Historically Calvinism has had to struggle with a necessary implication of the Irresistible Grace model: If God's call to the unelect is not genuine then He has also chosen (and even created) certain people to damn to eternal torment even though they never could have had the option to choose Christ. Modern Calvinists have recognized this is contradictory to God's moral character and have attempted to retain God's responsibility for election but remove his responsibility for the damnation of the reprobate by appealing to God's permission of the choice to sin. On this view, God did not cause the Fall of Adam and Eve (called "supralapsarianism") rather God permitted the Fall to happen (called "infralapsarianism").While this model retains consistency in God's moral character, it requires either the contradiction of a key Reformed tenet or denial of permission altogether (the distinguishing feature of infralapsarianism). All things that happen are decreed according to God's good pleasure. However, in infralapsarianism reprobation is conditionally or unconditionally decreed. If the former, then it is not according to God's good pleasure (the contradiction); if the latter, it is not according to God's permission (the denial). There is no other logical option. This forces the infralapsarian Calvinist to either jump back and forth between supralapsarian Calvinism (which makes God the cause of the Fall and sin) or Arminianism (which posits that God merely had foreknowledge of the Fall and sin). As many supralapsarians and Arminians have pointed out, these issues are not merely paradoxes that have some undiscovered, logical way to be reconciled (an appeal to mystery would suffice in such a case), they are logical contradictions within the infralapsarian model (an appeal to mystery is unsound thus not acceptable). However, many people also see the contradictions in the supralapsarian and Arminian options.

Keathley argues that what the Calvinist attempts but logically fails to accomplish in infralapsarianism (consistency in God's moral character and His sovereignty over all reality) Molinism actually accomplishes without any logical contradiction between God's meticulous sovereignty and man's libertarian free will. The Overcoming Grace model posits that while man is so fallen in his sin that he cannot make the choice on his own to accept Christ, that the Holy Spirit works his on heart in a way that can overcome that inability yet the work can still be stubbornly resisted. Why any person would resist God's grace does remain a mystery (a paradox but not a contradiction given man's fallen state) in the Overcoming Grace model; however, unlike the Irresistible Grace model that places the mystery in God's moral character, the Overcoming Grace model places the mystery in man's illogical, evil choice. Since Scripture denies that God can be immoral, but it affirms that the unsaved man is both illogical and evil, the latter mystery seems to be more in keeping with the witness of Scripture. Thus, while infralapsarianism is logically inconsistent, and supralapsarianism holds Scriptural passages that affirm God's permission to be metaphorical at best (since permission is illusory), Molinism remains logically consistent while completely affirming the literal truth of all scriptural passages that affirm God's permission.

Chapter 6: E Is for Eternal Life

One of the great struggles in attempting to model the coexistence of God's sovereignty and man's free will has been the assurance of salvation that any individual may have. In Calvinism the elect have assurance of salvation, but no individual knows if he is elect (that knowledge is part of the hidden will of God). In Arminianism, while an individual knows that they have salvation at that moment, they have no assurance that they will persevere in the faith. Since Scripture teaches that those saved will produce good fruit (good works), both Calvinists and Arminians end up grounding any hope for perseverance to good works. While neither of these models can be accurately described as teaching "works-based" salvation (a common but inaccurate accusation), they can be accurately described as teaching works-based assurance of salvation.Keathley argues that assurance is not found in the sanctification of the believer (thus is not works-based) but rather in the justification of the believer. Justification takes place simultaneously with the moment of salvation, and since Scripture also teaches that the elect will persevere, assurance is provided at the moment of justification. So in the Eternal Life model, the individual believer has confidence that they are one of the elect (unknowable to the Calvinist) and that they will persevere in the faith (unknowable to the Arminian).

This model, of course, does not come without its challenges. While much of Scripture teaches that the elect will persevere, some verses also seem to teach that apostasy (losing salvation) is a real possibility. There have been several different approaches taken to interpreting these passages (even among Molinists). These approaches generally fall into three categories: apostasy is possible, apostasy is not possible, and apostasy is threatened but not possible. Keathley describes the various options within each of these categories and the challenges that do arise Scripturally and philosophically with them. Though some passages teach that apostasy is possible, Keathley argues that apostasy will not take place because perseverance is presented throughout Scripture as a promise to those saved not as a requirement of those saved. Competing Molinist positions hold that those apostasy passages serve as a means of perseverance (an encouragement to good works- not necessarily a bad thing, in an of itself), but that still ties assurance back to the sanctification of the believer, making perseverance a requirement for assurance of salvation. The Eternal Life model presented by Keathley properly grounds the believer's assurance in God's unchanging character rather than man's constantly changing struggle with sin.

Chapter 7: S Is for Singular Redemption

Many Calvinists hold to only four petals of the TULIP. When a believer describes themselves or someone else as a "four-point Calvinist," it is generally understood that the Limited Atonement doctrine is the one dropped. The Calvinists who do accept this doctrine argue that the atonement of Christ was limited only to the elect and never available to the nonelect (one can see the logical connections to other Calvinist teachings here as well). Many Calvinists reject this doctrine because of the many passages of Scripture that teach that God loves everyone and authentically provides a way for everyone to receive salvation if accepted. This results in an alternate view called "Unlimited Atonement" for obvious reasons. Of course, the debate over the extent of Christ's atonement is not limited to Calvinists, it is an important part of models proposed even in Arminianism.While both the Limited Atonement and Unlimited Atonement doctrines can find many biblical passages to support the respective views, both must also reject the "proof texts" provided by the other position. Keathley proposes that an important distinction has been overlooked in this debate: the distinction between the provision of salvation and application of salvation. The Singular Redemption model proposes that, like the Unlimited Atonement model, Christ's death and Resurrection provided salvation for every person; however, like the Limited Atonement model, it recognizes that that salvation is only applied to those who have freely chosen to accept the provision (the Elect). This model accepts the biblical data that evinces both models, and while doing so it maintains internal logical consistency.

After explaining the distinction and how it reconciles the biblical texts, Keathley provides five more biblical and philosophical arguments and emphasizes the many areas of agreement with the proponents of both competing doctrines. He concludes the chapter (and book) with a short summary and emphasizes that Molinism succeeds in retaining the biblically supported tensions between the certainty of God's sovereignty and man's libertarian free will and between the believer's confidence in salvation and the urgency of the Great Commission.